There’s a little perfectionist living inside of me. He has been here for years.

In school, the perfectionist ensured that I studied thoroughly and got the best grades while staying out of trouble, which was definitely useful, albeit perhaps not the most fun.

But he also made me study each page of the textbook until I understood it perfectly, which was overwhelming. I was expected not only to earn the best grades but to also get a perfect score. Because of that, I was feeling disappointed if I got the best grade but scored only 95%!

I eventually began working as a software engineer. My perfectionist didn’t hesitate to remind me to design solutions perfectly, think about all the edge cases, write the best code possible, and test the code thoroughly before submitting it. That allowed me to progress quite quickly as I delivered well-written code.

But I was also getting increasingly more worried. What if my code is not perfectly clean? What if I missed a bug? What if I didn’t think of all the edge cases? What if I didn’t write the best possible solution?

The two sides of perfectionism

I learned that perfectionism has a good and a bad side, and there seems to be a very fine line between them.

The good side

On one hand, perfectionism can help us deliver high-quality work.

It pushes us to think about the future consequences of our actions (as well as the actions of others), predicting potential mistakes and edge cases, resulting in the best possible decision.

It makes us test and document our code thoroughly, which can save the time of our future selves and our colleagues.

It can be very useful when working on front-end projects where the design has to be pixel-perfect. By spotting small imperfections early, the time spent on iterating the product with the quality assurance team can be significantly reduced.

A little bit of perfectionism can also help us provide good quality feedback to ourselves, our colleagues, as well as to the product that we are working on. In a world with scarce feedback, spotting small imperfections and opportunities for improvement can go a long way!

The bad side

On the other hand, perfectionism can slow us down, and make us worry needlessly.

We can end up spending too much time on a task, because we want to make it perfect, even though it’s not necessary. This can be a problem on a project with a tight budget and a short deadline.

Perfectionism is often the cause of procrastination - we can end up never starting a project or a task because we are scared that we won’t be able to do it perfectly or we don’t know enough to finish it. This can also lead us to endlessly learn and watch tutorials without ever building anything (the so-called tutorial hell).

It can also make us worry needlessly, such as worrying about the future consequences of our actions, even though they are unlikely to happen, or worrying about the quality of our work, even though it’s good enough. Over time, this can lead to a negative self-image and impostor syndrome.

Taking control of perfectionism

I’ve had a lot of internal monologue with my perfectionist, and while I don’t think he will ever go away, I’ve learned that I can leverage him so that I can take advantage of the good side of perfectionism while avoiding the bad one. This requires self-control, self-awareness, and understanding of the situation.

Here are some of the strategies I’ve learned to use perfectionism to my advantage.

Understanding the future consequences

Let’s take a classic example from software engineering - naming a function.

A lot of time can be spent on choosing a name for a function. It must be descriptive, but not too long. It must be simple, but not too simple and general. It also must be consistent with other functions.

Naming functions with these requirements in mind is great, but it can make us spin in circles trying to find the perfect name. Every time we think of a name, we feel like we can do better. When we do find something better, the cycle repeats.

In such situations, I first take a step back and realize that I’m starting to spin in circles. I take a deep breath, and then ask myself the following question:

“What are the future consequences of going with the non-perfect solution here?”

In the example of naming a function, the non-perfect solution is choosing a suboptimal name. What are the future consequences of that?

Well, it depends. If the function is used in one place (which is written by me), and the name is not too bad, then the consequences are probably not that bad. If the function is used in many places or it will be used by other developers, and the name is really bad, then the consequences can be quite bad.

In the first case, I can go with the non-perfect solution, and then refactor it later if it turns out to be a problem. In the second case, I should probably spend more time on finding a better name.

What can also help here is looking around a little. Sometimes we get too obsessed with the function we are currently naming that we forget that all around us are functions we named imperfectly some time ago, and we are able to work with them anyway. So it might not matter if we name this function imperfectly as well, as long as we name it well enough that we’ll be able to work with it in the future.

All in all, it’s important to understand the future consequences of the decision and adjust our perfectionism accordingly.

Tracking the imperfections

I often find myself working on projects with urgent priorities and tight deadlines. In such situations, there is no time for perfect solutions, which can make my inner perfectionism scream in agony. This can be a big liability if it is not put under control.

What I’ve found is that my inner perfectionist doesn’t necessarily need everything to be perfectly done, it just must be perfectly tracked. In other words, my inner perfectionist hates leaving stuff behind.

So what I found works really well is to track all the imperfections and improvement opportunities that I find. I usually use a project management tool on the project (for example Jira or Trello) to make tickets and put them in the backlog. This has multiple benefits:

- My inner perfectionist is happy.

- I can focus on what really matters for the delivery.

- Me and my team have a better overview of the technical debt on the project.

- The client is aware of the tradeoffs we took and can make an informed decision on whether to pay off the technical debt or not.

Practicing imperfectionism

Whenever I get the chance, I build a quick personal project, either exploring a new technology or solidifying what I already know.

On such occasions, I sometimes practice imperfectionism - I deliberately hack together a prototype rather than implementing a sophisticated solution. The idea behind this is to train my “quick and dirty prototyping” muscle. When my inner perfectionist starts screaming, I try my best to ignore it and keep moving forward.

Why can this be useful?

It is true that in most of the professional software development, we want to focus on good solutions without taking shortcuts or implementing hacks, but there are times when we need to hack together a quick prototype for a demo or make a (god forbid it) last-minute hotfix to production. In such situations, I don’t want my inner perfectionist to slow me down and let my team down.

Training my “quick and dirty prototyping” muscle can help me deliver a quick solution when it’s needed, and then refactor it later when there is more time.

Making peace with imperfections (sometimes)

Life is imperfect. And so is the code that we write - no matter how hard we try, we will eventually end up with suboptimal pieces of code. My inner perfectionist keeps this in mind and often makes me worry about certain pieces of code.

However, my inner perfectionist also likes to negotiate. If I present a good case for why something imperfect is just fine as it is, I might earn myself one less thing to worry about.

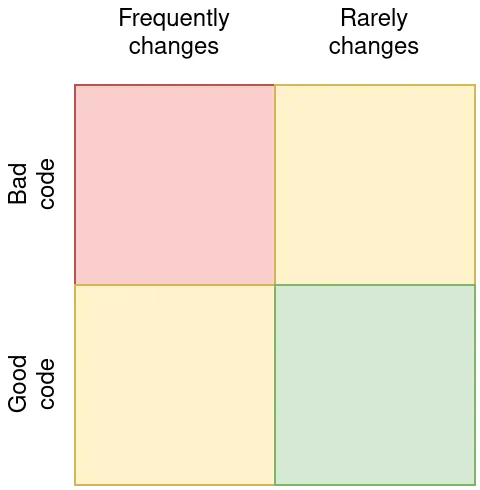

When it comes to code, it’s good to think about it in terms of the modified Eisenhover matrix.

There are four quadrants:

- Code that is bad and frequently changes

- Code that is good and frequently changes

- Code that is bad and rarely changes

- Code that is good and rarely changes

It is evident that the most important quadrant to worry about is the bad code / frequently changes one. However, we often spend worrying about the quadrant with much lower priority - bad code / rarely changes.

Modern software development is fast and we often cannot afford to fix things that rarely change just so we can feel better about it. If a piece of code is bad, but it works and it hasn’t been changed for 2 years and there are no plans to change it in the foreseeable future, then presenting such a case to my inner perfectionist can make him at peace with this particular piece of code, freeing my mind to worry about more important imperfections.

Activating the perfectionist

I’ve spent the entire post talking about how to silence the inner perfectionist. However, when the time is right, he should be let out!

He should think about the edge cases, plan out the implementation diligently, and iron out the little quirks in the product to make sure it’s all perfect for customers.

Here are some situations where perfectionism can come in handy:

- Building a pixel-perfect UI

- Planning the architecture of a project

- Assessing the quality and usability of a product or a feature

- Providing constructive feedback to my colleagues

- Building mission-critical software

When to be a perfectionist?

When is the right time to activate the perfectionist? If we let him out too often, he can slow us down. If we don’t let him out often enough, we can end up with a low-quality product.

This is why I make sure to always set up expectations with my clients. I like to ask questions, such as:

- “Should the UI be pixel-perfect?”

- “Do you need this to be released as soon as possible with the minimum viable amount of features or should it be feature-complete?”

- “Would you like me to invest a lot of time in planning this perfectly or do you want a quick implementation to test the market?”

- “Is this a prototype or a mission-critical system?”

Such questions are vital so that we understand the business goals of what we’re building.

We shouldn’t cut corners when building production-grade mission-critical software that will be used by millions of users. We also probably shouldn’t spend 2 weeks planning out the architecture of a product that will be shown to a few beta testers to get an initial taste of the market.

The business goals indicate when the perfectionist needs to come out and when he should be silent.

Conclusion

I went through many phases in my life when it comes to my relationship with perfectionism.

I was initially taught that perfectionism is great because having good grades in school is important.

Then I learned that perfectionism is bad because it can make me worry too much and slow me down.

Now I’m learning how to control my perfectionism so that I can enjoy the good side of it while avoiding the bad one. This blog post illustrated some of the strategies that I use to do that. I’m still at the start of the journey here and I’m curious to see what the future will bring for me and my little perfectionist.

Thank you for reading!